I had barely turned ten when I heard that there was such a thing as a heretic. In my neck of the woods, the biggest heretic was a wederdoper (re-baptizer). A group of them was a sekte, and they were to be avoided like the Bubonic plague.

I had barely turned ten when I heard that there was such a thing as a heretic. In my neck of the woods, the biggest heretic was a wederdoper (re-baptizer). A group of them was a sekte, and they were to be avoided like the Bubonic plague.

There were also other sects: Pentecostals, JWs, SDAs, Mormons, and so on. They were all equally dangerous, and equally lost. That was the consensus at the time, as we all understood it, and it lasted well into my high school years.

Until one morning, during a compulsory Sunday School class before the church service, when our dominee revealed a somewhat more open-minded approach. He took a piece of chalk and drew two large circles on the blackboard. Like the Audi rings, they overlapped, but barely. He pointed to the left circle.

“That’s us.”

He pointed to the other circle.

“That’s them – the Pentecostals.”

His finger slid to the minute overlap, which bore a remarkable resemblance to the eye of a needle.

“It is possible that there are true believers amongst them, and they will be found here.”

Not long after that, my older brother, who had recently become a “born-again” Christian, forced me (literally) to accompany him to a Pentecostal church service. I was surprised to discover that these folks were nothing like the treacherous apostates I had been warned against. The singing was great and the love was tangible. I ended up staying.

One of the first things I learned was that the real heretics were the gereformeerde people. They baptized infants and did not believe in the gifts of the Spirit. The Bible differed with them on both accounts, and that settled the matter. “We are the oldest denomination on earth,” the Pentecostals said. “We trace our roots back to the church of Acts.”

It was a relief to learn that I had not become a heretic, but that I had in fact escaped from them. The downside was that it seemed that my entire Reformed family had suddenly lost their salvation, and were in desperate need of redemption.

The passion that I found amongst the Pentecostals led me all the way to seminary. I wanted to be the best pastor ever, and gave it my everything. But in my final year something happened that would alter the course of my spiritual pilgrimage yet again: I stumbled upon John MacArthur’s Charismatic Chaos, and devoured it.

I was a heretic, after all. A vile and horrid one. MacArthur’s book made sense, and clarified a number of things that I had become uncomfortable with in our denomination. Chief amongst them was the outbreak of the so-called Toronto Blessing – the laughing revival that had been exported to the USA by South Africa’s Rodney Howard Brown, and that had returned to our shores thirty times stronger. Phenomena like this were all just over-the-top fanaticism, MacArthur taught me. Like the Pentecostal lady who taught her dog to bark in tongues.

MacArthur represented a new hybrid of Christian. He was the best of both my former worlds: Someone who understood repentance and baptism, but was wary of fanaticism – a type of Reformed Evangelical. I began reading everything by him that I could lay my hands on, and even distributed a copy of Charismatic Chaos amongst my Pentecostal congregants. (By now I was an ordained minister.)

The Senior Pastor was not amused, to say the least.

Needless to say, the cognitive dissonance soon became unbearable. After a number of ministerial years in my Pentecostal denomination, I resigned and became a Baptist. That was the closest thing to a MacArthur denomination that one could find here in South Africa.

However, I soon learned that not all Baptists could be trusted. Some of them were not like MacArthur at all, I was told. They were Arminians. Arminians were people who misunderstood grace. And yes, you guessed it. Arminians were heretics.

Sigh…

The good news was that there existed an antidote to Arminianism: Calvinism. That was MacArthur’s secret, and it left me with no choice. I quickly gravitated towards the non-Arminian Calvinistic fraternity within my new denomination, only to discover that they had the habit of fraternalising with non-Arminian Calvinists from other denominations, many of whom were passionately committed to the doctrine of infant baptism.

My passion for purity had made me delirious, it seemed. Like a lost soul in the desert, my ecclesiastical wanderings had taken me full circle to where I had begun. I was now attending conferences with paedobaptists (the fancy name for people who baptize babies) who believed that Pentecostals were heretics. It all seemed too familiar.

At one of these conferences I managed to corner Joel Beeke, one of the most respected Reformed theologians in the world, a renowned expositor of John Calvin’s writings, and an all-round nice, godly guy. I told him about the church of my youth, and he used the term “hyper-covenantalism” to explain how my old dominee’s theology differed from his.

I liked Beeke, so I decided that I was also going to become a non-hypercovenantalist. But before I had time to consider whether this label would suffice to put a distance between me and the heretical religion of my youth, a friend stuck a book in my hand. “It’s a gift,” he said.

The book was Dave Hunt’s What Love Is This? I started reading, and it did not take long to get the message: Calvinists were heretics. All of them, regardless of their levels of covenantalism.

The cognitive dissonance was back, with a vengeance.

I soon realized that the only way to rid myself of it was to write the inevitable Dear John letter to Calvin, although my ultimate decision to do so involved significantly more than what I had learned from Hunt’s book.

Let me pause for a moment and explain this. It is a maxim amongst Calvinists that non-Calvinists are non-Calvinists because they do not understand Calvinism, and that Dave Hunt, especially, does not understand it. This is quite befuddling, as Hunt spent more time studying it than just about anyone on the planet. But that’s besides the point. You never critique Calvinism based on a mere reading of Hunt. NEVER. Unless you enjoy evoking the Calvinistic stare that comes with recognizing a theological fruitcake (a mixture of horror and pity).

The reason, I suspect, has to do with the fact that Hunt’s book speaks more to the heart than the head. That makes it beautiful, and more than convincing for any sensitive soul, but it also also makes it inadmissible as evidence in the courts of Calvinism. Calvinism, as you may have heard, is severely left-brained. Humanitarian considerations are not at the top of their list, which is why early Calvinists had no problem to drown, torture or fry people who disagreed with their theology. As a result, I had to think hard and deep before making my exit. (I spoke about it here.)

Back to the story…

So who was Dave Hunt? My bridges were now burning ferociously behind me, and I was eager to find a resting place for a rapidly wearying soul. At this point my effort to escape from heresy had been going on for well over two decades.

Hunt was difficult to pin down, which made him interesting. He could probably be best described as an ex-Charismatic (although not Cessationist) with Brethren tendencies (he grew up in a Plymouth Brethren family.)

Now here was an interesting group of people: The Brethren. I liked their severe dislike of denominationalism, but disagreed with their end times theories. These they got from one of their founding members, John Nelson Darby, the man known as the father of Dispensationalism and Futurism. Another Brethren writer, Cyrus Ingerson Scofield, popularized Darby’s eschatology with his reference Bible that remains a sensation to this day, especially amongst Independent Fundamentalist Baptists.

Did I mention that I once explored the IFB in my desperation to settle down in a church family? This was during my early Baptist days, before I tried to be a Calvinist. One night a good brother from the United States looked me straight in the eyes and said in a no-nonsense voice: “The litmus test of Christian orthodoxy is your Bible translation!” He was, of course, referring to the KJV 1611 Authorized Version. I was using another translation. I was a heretic. That settled it.

And so, during my flirtations with the IFB, Darby’s eschatology was everywhere. They regarded the doctrine of the “rapture” (in the sense of it being a distinct and separate event from the second coming of Christ) as almost on the same par as the KJV issue. But I remained unconvinced, especially after reading Hendriksen’s More Than Conquerers, Greer’s The Momentous Event, Robertson’s The Israel of God (all of them Calvinists, for some or other painful reason), and so on.

Now rapture views were popping up once again – this time round in Brethren literature. Did this make them heretics? I decided that it did not. It was an honest mistake, and could be forgiven. (My wife also believes in the rapture, which contributed to my decision. Who wants to be married to a heretic?)

However, even though the Brethren started off well and their eschatology was forgivable, they ended up stepping into the very trap that they were speaking out against. They became progressively exclusive and elitist, and eventually split into two factions – the “Exclusive” and the “Open” Brethren – each firmly convinced that the other had succumbed to the spirit of…heresy.

Double sigh…

My ecclesiastical wanderings sort of fizzled out at this point, and were replaced with an exploration of everything non- (or post-) institutional, house-churchy, organic, relational, simple, and so on. Throughout, I remained passionately committed to the belief that somewhere, some day, I would stumble upon that non-heretical group of Christians who had been eluding me since infancy.

Sadly, I discovered that the non-institutional church world was oftentimes just a microcosm of the one I had fled from, with its own gurus, schisms, weird beliefs, rituals, claims of exclusivity, and so on. In fact, I learned that for every denominational atrocity under the sun there existed a myriad of spawns who perpetuated the atrocity somewhere in a house under the guise of being a purer or restored version of whatever it was that birthed the original movement in the first place.

And, of course, they all fled the mother ship with one express purpose: To get away from… the heretics.

At this point I ran out of sighs.

Yet I was not ready to give up. I could not shake the feeling that there was something disturbingly familiar about the observation that the passion to escape from heresy seems to lead to the inevitable dissemination of heresy. We were all too much like the delirious man who got quarantined for Jungle Fever – along with his fellow travellers who all picked up the deadly disease – and then decided to get away from them as he no longer wanted to associate with a bunch of people who were clearly not well. His escape provided him with the illusion of freedom and normality that he so earnestly craved, but his only real accomplishment was to spread the dreaded disease wherever he went.

I thought deeply about this, and then I remembered something that I haven’t told you, and found my answer:

Each group that I had ever explored in my yearning to escape from heresy was spectacularly shattered into its own bits and pieces.

When I encountered the Pentecostals In the 80’s, they were split into the middle-of-the-road Charismatics like the Hatfield Baptist Church of the Ed Roebert era, the Brook House guys next door (that story would fill a book), the Word Faith Churches like Rhema, the SA Vernuwingsbeweging with their churches, the Tent Revival Meeting styled classical Pentecostals like Nicky van der Westhuizen (no relation), and official denominations like the PPC (Pentecostal Protestants), AFM (Apostolic Faith Mission), FCC (Full Gospel Church), AoG (Assemblies of God) and the Spade Reën churches.

I visited all of them. Sometimes I joined them. I attended their conferences, read their literature and listened to their tapes. I studied them. I experienced them to the full. I made friends in them. I got to know a number of their leaders.

And, of course, I always managed to find out why each of these streams was regarded as heretical by someone, somewhere.

When I joined the Calvinists, I witnessed the same phenomenon. And I witnessed it amongst the Fundamentalists. And the Baptists. And…and…and…

And then I thought of an old joke…

Once I saw this guy on a bridge about to jump. I said, “Don’t do it!” He said, “Nobody loves me.” I said, “God loves you. Do you believe in God?” He said, “Yes.” I said, “Are you a Christian or a Jew?” He said, “A Christian.” I said, “Me, too! Protestant or Catholic?” He said, “Protestant.” I said, “Me, too! What denomination?” He said, “Baptist.” I said, “Me, too! Northern Baptist or Southern Baptist?” He said, “Northern Baptist.” I said, “Me, too! Northern Conservative Baptist or Northern Liberal Baptist?” He said, “Northern Conservative Baptist.” I said, “Me, too! Northern Conservative Baptist Great Lakes Region, or Northern Conservative Baptist Eastern Region?” He said, “Northern Conservative Baptist Great Lakes Region.” I said, “Me, too! Northern Conservative Baptist Great Lakes Region Council of 1879, or Northern Conservative Baptist Great Lakes Region Council of 1912?” He said, “Northern Conservative Baptist Great Lakes Region Council of 1912.” I said, “Die, heretic!” And I pushed him over.

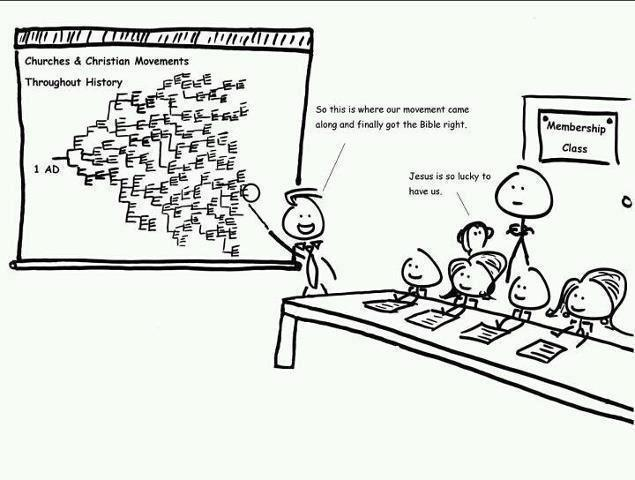

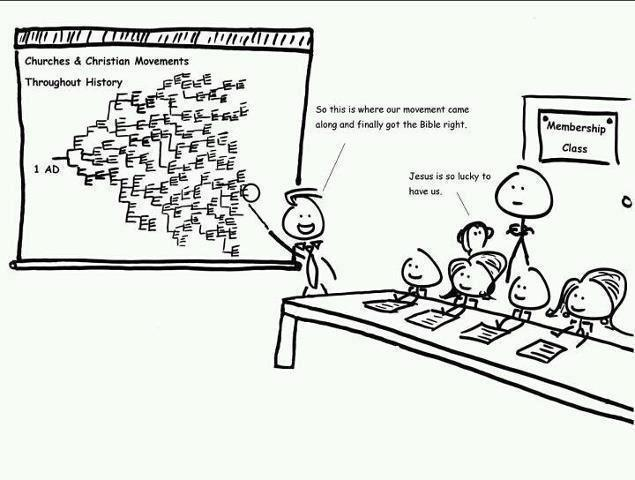

…and an old cartoon…

… and I finally got it.

I am a slow learner. It took me over three decades to smell the rat. Clearly what I was looking for did not exist. The moment I realized this, I realized that there was something dreadfully wrong with the way in which I had been defining the word heretic.

More about that in the next post.

(PS: I made a promise to write a third post in the series The Church of No Anticipation during 2018. I have not forgotten, but I am still thinking through that one.)

On that fateful day, 27 October 1553, on the plain of Champel at the gate of Geneva, whilst the flames were engulfing Michael Servetus, he used his last breath to cry out in a loud voice, “O Jesus, Son of the Eternal God, have pity on me!” The words were ignored by the bystanders, and Servetus died soon afterwards.

On that fateful day, 27 October 1553, on the plain of Champel at the gate of Geneva, whilst the flames were engulfing Michael Servetus, he used his last breath to cry out in a loud voice, “O Jesus, Son of the Eternal God, have pity on me!” The words were ignored by the bystanders, and Servetus died soon afterwards.

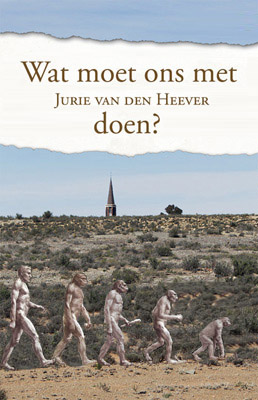

I have never been to one of Angus Buchan’s meetings.

I have never been to one of Angus Buchan’s meetings.